I was impressed by how tech ecosystems in different markets have come together during the COVID-19 crisis. It is truly amazing and inspiring. From where I stand, I figured that one small way of contributing to this initiative is by trying to demystify the not-so-exciting world of term sheets, especially in a context where financing rounds might be turning to VCs’ advantage. 😅

There are amazing resources out there (i.e. Venture Deals, Secrets of Sand Hill Road) that explain term sheets in great detail and much better than I could ever do, so the last thing I would like to do here is explain every term for the hundredth time. Instead, l will pinpoint the four key terms that always come up during negotiations in plain English and in a visual fashion (when possible). I anticipate these terms will become even more so a source of misalignment in the next 18 months.

I will start by admitting that when I joined the VC world, two things surprised me about term sheets:

1. Most of the time nobody wants to look naive and unprofessional, so everybody pretends that they fully understand all the terms and what is going on.

2. It is actually pretty hard to learn about term sheets as the only “efficient” way of becoming really familiar with how they work is to see them in action; by either offering a term sheet (investor) or by receiving one (entrepreneur).

As Brad Feld and Jason Mendelson mentioned in their book Venture Deals, if you are negotiating something other than economics and control, you are basically wasting your time. Let’s focus on four terms that fit these two categories:

1. Liquidation preference

We can start with what is safe to call “one of the most important terms in a TS”: liquidation preference. In simple words, the liquidation preference defines the priority in which shareholders get their money back (“last money in, first money out”) at a certain multiple after a certain liquidation event (i.e. merger, IPOs, bankruptcy, change of control of the company, etc.). For instance, if you own preferred shares of a company, you will get your money before all the other common shareholders in the company. In terms of multiple, market standards in Europe are typically 1X of original investment but I have seen up to 3X in some aggressive sheets.

So far so good but here comes the tricky part: being able to identify whether it is a participating or a non-participating preferred stock clause. The good news is that most of the TS today use non-participating preferred stock clauses but it is still crucial to understand the difference between the two.

Non-participating preferred stock

The investor has the option either to take the original amount of his investment in the company (preferred shares) OR to take the amount of money based on their % of the ownership of the company (converting preferred shares into common shares).

Participating preferred stock

The investor will take the original amount of his investment in the company + take an extra amount based on his % of the ownership of the company on the remaining money left after his original amount has been deducted. (Not really entrepreneur friendly as you can imagine).

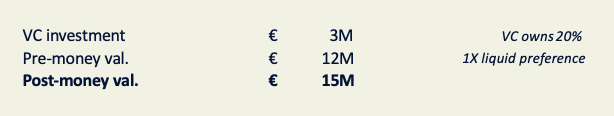

Let’s take a simple example to illustrate both scenarios from an entrepreneur’s perspective. As a starting point, we will assume that:

(1) You are the founder and CEO of a startup and your Series A investor owns 20% of your company after an investment of €3M (€15M post-money valuation) with 1X liquidation preference. 😎

(2) After your Series A, you have an offer on the table to sell your company for €20M 🎉

OPTION 1 – Non-participating preferred stock:

In this case, your investor can either decide to take (1) €4M off the table (20% ownership) OR (2) her original investment of €3M. It is a no brainer but the investor has the option.

In the context of a sale with a valuation lower than the initial post-money valuation of €15M, say €10M, your investor still has the option to choose between taking back her original investment (€3M) OR her 20% ownership, which would result in €2M. Again, a no brainer.

OPTION 2 – Participating preferred stock:

The investor will receive €3M (her initial investment) first and then, out of the €17M left (€20M – €3M initial investment), she will also take 20% of ownership. This will amount to an additional €3.4M. In total, your investor will take €6.4M (€3M + €3.4M) from this liquidation event. A good (and nasty) move for the investor; not so much for you, right?

– Again, in the context of a sale with a valuation lower than the initial post-money valuation (€15M), say €10M (to use the same number), the same logic applies. €3M (initial investment) + €1.4M (20% ownership of new valuation €10M – €3M = €7M) = €4.4M for your investor.

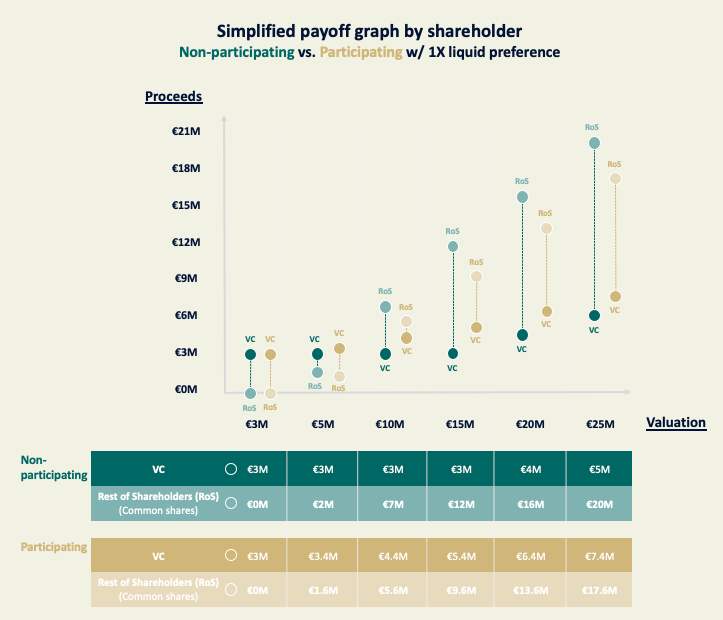

For the ones who are more visual (like myself), here is a payoff graph to visualise the relationship between proceeds and valuation in both scenarios. It is easy to see that:

1. non-participating preferred stocks are much more entrepreneur-friendly

2. a valuation below €15M for non-participating preferred stocks does not impact the VC investor in terms of proceeds, while it is different for the rest of the shareholders (common shares), who should look for a valuation higher than €3M to receive any type of proceeds (even the smallest).

So, as a founder and CEO of a startup, which liquidation preference clause would you rather accept in your term sheet? 🤗

2. Vesting

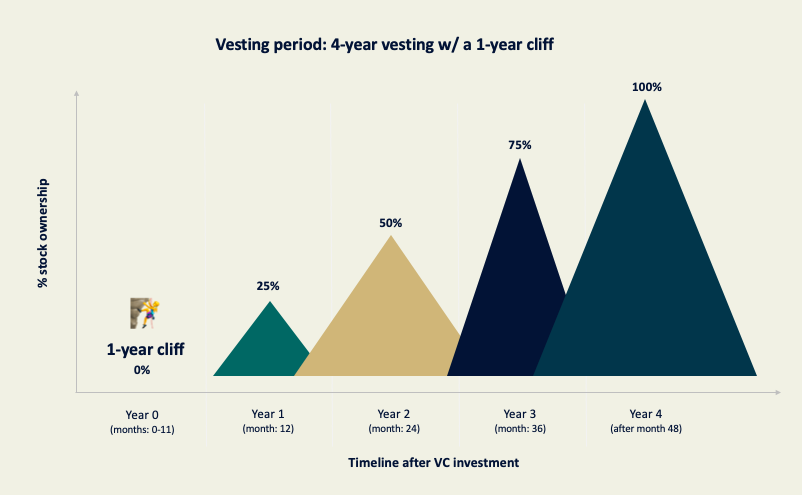

Let’s continue to the second term: Vesting. Basically, it means that founders and employees unlock a certain % of their ownership over a period of time defined in the term sheet by the investor (it is usually a 4-year period with a 1-year cliff). For employees, equity is often rewarded as a compensation for low cash compensation in exchange for a potential upside of share price in the future. Today, we will focus on founder stock vesting, which is extremely more relevant during times of uncertainties.

Referring to the graph above, if all goes according to the plan 💅, you as the CEO and founder will own 25% of your common shares after year 1, then 50% after year 2, 75% after year 3, and finally you will own 100% of stocks after year 4.

However, if it doesn’t go according to the plan 😨 and you leave the company within the first 11 month (year 0), you will leave with nothing as none of your common shares have been vested. Your remaining unvested shares will then be canceled or redistributed to the option pool for instance.

Let’s take a third scenario: just to make sure everybody is on the same page. If you leave as a “good leaver” before month 36 (year 3), you will have vested 75% of your common shares, and 25% of your unvested shares will be purchased by the company, canceled or redistributed to the option pool. You will lose your remaining 25% (year 4).

What does “good leaver” mean? In most cases, founders are considered “good leavers”, unless there is a resignation, a misconduct (fraud), a break in an obligation that will trigger the termination of the employment contract and the loss of her shares, thus making them “bad leavers”.

Hence, the 3 key aspects of a vesting clause that you should care about are:

1. Vesting period of shares: number of years and cliff

2. Remaining unvested shares

3. Circumstances of departure (good or bad leaver)

This term is often a source of misalignment during the negotiation between the VC and the founders. From a founder’s perspective it might seem unfair because the rationale usually is: “it is my company and I have been working hard since day 0, so why should I temporarily lose my shares?”. It is a fair argument.

Let me try to offer a counterargument from an investor’s perspective and explain why it is an extremely important clause. When taking a bet in an early-stage startup, the actual bet is taken on the founders and their ability to deliver the promised vision and results in the future. In a Seed or Series A investment context, the founding team is the key element of the bet. If I had to put a score/weight on this element, I would say the founding team represents at least 50% of the bet). Therefore, removing or weakening this part, decreases considerably chances for early-stage success.

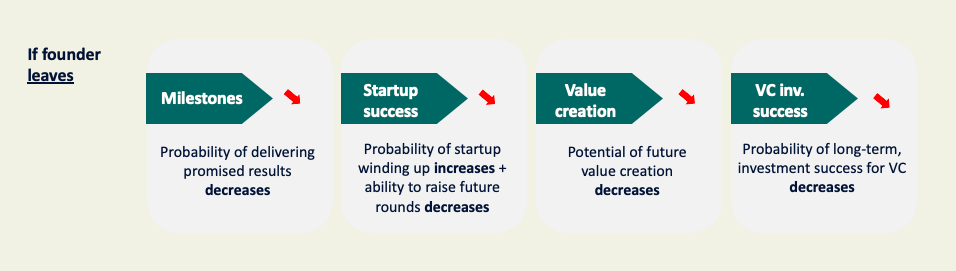

This is how I visualise the impact chain of a key founder leaving a VC-backed startup. It is an imperfect process that overlooks some parts like company culture, employee motivation among other things, but I think it still gives a general understanding of how the VC investor might be impacted.

Naturally you may ask, what about replacing the founder(s) who is/are leaving? Sure, it is the logical next step and in some cases finding a new replacement works. But to be honest, it is far from ideal as it is a very challenging thing to do. Founders are the soul of the company, so if the soul leaves, the company will probably die. It is as simple as this.

It is key to see vesting as a mechanism for investors to (1) increase founders’ commitment, (2) incentivise them to stay as long as possible in order to create as much value for the company as possible, and (3) increase early-stage success.

3. Anti-dilution provision

This third key term comes into play, usually when the 💩 hits the fan.

The anti-dilution provision (ADP) protects the investors from dilution in case of down rounds with new shares issued at a lower price than what was originally paid by the investors. Basically, this clause allows price per share for preferred shares to be adjusted to this new down round. (Note: common shareholders do not have such mechanisms).

When a VC invests in your early-stage company, she basically wants the valuation to keep increasing, mainly through future rounds of financing. If that doesn’t happen, the anti-dilution provision is a “schmuck insurance” as Scott Kupor describes it in his book “The Secrets of Sand Hill Road”.

Let’s see how it works in real-life by taking the same example in liquidation preference (see above) but for a down round this time.

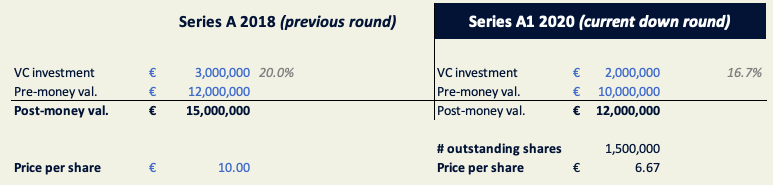

1) You are the founder and CEO of a startup and your Series A investor owns 20% of your company after an investment of €3M (€15M post-money valuation) with 1X liquidation preference. So far so good.

2) After your Series A, things are not going as planned (quite the opposite in fact) and you need to raise a down round in order to survive. This new round of €2M puts your post-money valuation at €12M (vs. €15M before). Nobody is happy but that’s life. 🥵

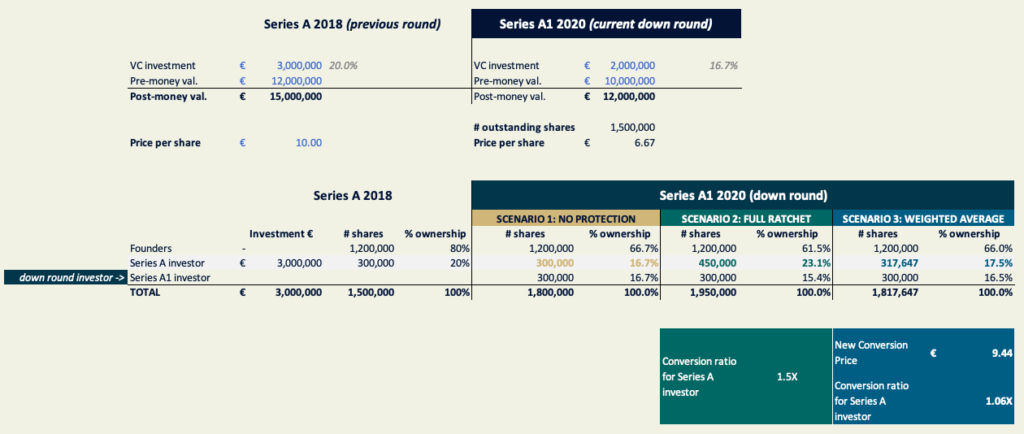

Now we can explore three different scenarios according to the provision type and their implications in terms of ownership.

Scenario 1: No protection

Scenario 2: Full-ratchet provision

Scenario 3: Weighted average provision

In this scenario, your investor has no protection at all and she will get diluted (preferred shares) at the same rate as you, the founder (common shares). As a founder, it is very unlikely that you will ever receive term sheets with no anti-dilution protection and even less so in the current climate (COVID-19), where the market is turning to VC’s advantage.

SCENARIO 2: FULL-RATCHET PROVISION

The price per share from the previous round will be fully reduced to the new price per share in the down round. Here, you need to find the conversion ratio in order to convert those existing preferred shares (previous round) to this new down round. It is calculated by dividing the original price per share paid in the previous round by the new price per share.

In our case, the conversion ratio is 1.5X.

Calculcation: €10 (price per share in our Series A) / €6.67 (new price per share in our Series A1 down round) = 1.5X

Quick note: while it is the easiest anti-dilution provision to calculate, this is also by far the most friendly provision for investors.

SCENARIO 3: WEIGHTED AVERAGE PROVISION

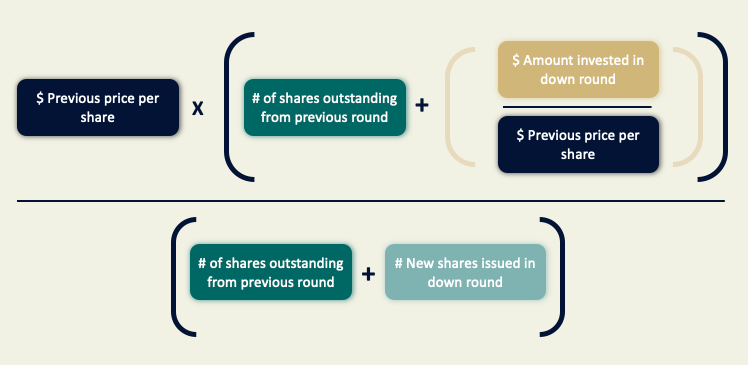

This provision is the fairest approach. It takes several variables into account to come up with a more equitable price per share and conversion ratio. The variables include the # of shares outstanding, the # of new shares issued in the new down round, the amount invested in the new down round, and the previous price per share paid.

Step 1: find the new conversion price, using this straight forward formula 😴:

Applied to our example, the new conversion price for our investor is €9.44 instead of €10 paid by the Series A1 down round investors:

€10 price per share from previous round x ( 1,500,000 shares + ( €2,000,000 as new investment / €10 )) / ( 1,500,000 shares + 300,000 new shares issued in down round) = €9.44

—

Step 2: find conversion rate (just like in scenario 2: Full-ratchet provision), using this formula: Original price per share paid in previous round / New conversion price

€10 / €9.44 = 1.06X

Cap table analysis

The main takeaway: the weighted average provision is the most entrepreneur friendly provision that investors typically use in term sheets. We should try to understand why.

The full ratchet scenario is the worst-case scenario for founders, as they experience a pretty tough ownership dilution from 80% to 61.5%. A nasty move; high dilution usually impacts motivation, commitment, and potential future rounds of financing in a significant way. The Series A investor is the “winner” of this down round as she ends up with more ownership than previous round (20% -> 23%), indirectly increasing her control over the company. This scenario is not ideal for the new investor in this down round either as he will end up with less ownership (15.4%) than in the other scenarios. It might even become a blocker to the transaction in some cases. If you think about it, the new investor is taking big risks to extend the runway and give the company an opportunity to pivot/execute its plan, so it must be worth the effort in terms of ownership.

Whereas the weighted average scenario looks very much like the no-protection scenario in terms of final % ownership, which is fair in my opinion. Founders are diluted less aggressively and in a more “equitable” way (80% -> 66%), just like all the rest of the shareholders: Series A investor is losing 3.3% of ownership (20% -> 16.7%). Regarding the new investor, he will end up with 16.5% of ownership, which is 1.1% higher than the full ratchet scenario scenario. This scenario seems relatively fair to everyone.

One small way to mitigate the dilution is to increase the size of the option pool in order to give back some common shares to the founders/employees post-round. This will dilute further the investor ownership but that might actually be a smart move in the long-run.

—

Most of VC investors use weighted average provisions and understanding the nuance between the two types is very important. As concluding remark:

(1) this provision only triggers in case of down round (= poor performance) so as long as you keep creating value, meeting your milestones and moving forward, this clause is harmless.

(2) dilution happens every time that a company issues new shares either for up or down rounds, so focusing on understanding the mechanisms in both scenarios (up or down rounds) is critical.

4. Drag along and tag along rights

The fourth term is about control (vs. the three previous other terms that are about economics).

(By the way, congrats on making it this far into this post. 👏 I know, I know, it is not easy 😬).

In short, drag-along rights give the majority shareholders (i.e. investors) the right to prevent minority shareholders from blocking a possible “transaction” (e.g. sales of a company or liquidation on a company) and move forward with the deal, even if the minority shareholders don’t necessarily want to. This term defines the % of shareholders (usually between 50% and 80%) who need to agree on an offer to be able to move forward. The good news is that it ensures that the same deal is being offered to all the shareholders.

This term is pretty straight forward, so as a founder, you should focus on the threshold (%) that determines if the rest of the shareholders will be dragged into (= forced) the transaction, and understanding who has rights on your cap table.

Say now that you have received an offer from Google to acquire your company. 🤩 Google would like to acquire 100% of your company and you know that some of your shareholders, (who own ~20% of your company), are against that transaction because they think it is too soon to sell.

As a founder, you need to get the approval of your shareholders who own usually more than 2% through a vote. Let’s assume that you need 60% of approval (threshold) to be able to accept the offer from Google. The final result is a 70% of “Yes, we want to sell to Google”. Great, you exceeded your threshold, so the Google deal will be happening. It will force the remaining 30% of the shareholders to sell their shares, including the ~20% of shareholders who were initially against that transaction.

Now let’s talk about the tag along rights.

Put it simply: this term is the opposite of drag-along. If a majority shareholder (investor) wants to sell his shares on his own (not in the event of an acquisition), resulting in the new buyer holding a majority of the shares in your company, minority investors have the right to follow him and get the same deal. The point here is to make sure that minority shareholders are protected and not forgotten.

In real-life: you have a majority shareholder on your cap table, who owns 50% of your company. This investor is a solo player who has sort-of lost interest in your company and he has found a buyer for his 50% who would like to sell his shares (not all the shares). If the minority shareholders feel that they are put in an unfair position in this transaction (“why is he selling and I’m not?”), they can use their tag along rights to force him – the major shareholder who owns 50% of the company – to work with them and include them into the sale.

We are done! It wasn’t that hard, was it? I have really tried my best not to make the not-so-exciting term sheet world more complicated than it already is, and I hope this has given you a first good taste.

To sum up, I discussed four key terms that usually come up during negotiation (i.e. liquidation preferences, vesting, anti-dilution provision and drag-along/tag-along rights) and I used concrete examples to illustrate each one of them as best as possible. As a final word on term sheets, I will just say that what really matters in term sheets is: economics and control. The rest is secondary.

Good luck with your next term sheet negotiation! 🤞

I would love to hear your thoughts, and your feedback is always appreciated so feel free to reach out. Thank you!